by Campbell Plowden

October 19, 2022

I first visited the village of Chino on the Tahuayo River in 2008 and had enjoyed a long, cordial and productive relationship with their artisans and community. We had bought hundreds of baskets, woven frogs, and other crafts, funded improvements to their local school and artisan building and donated supplies of food and medicine during the peak of the pandemic. Artisans had participated in our full series of artisan training, organization strengthening, natural resource management and Alternatives to Violence Project workshops.

In the past few years, though, interest in participating in our sponsored activities was declining, and things hit an all-time low during my last visit in March when we had a difficult discussion about the pricing of baskets and they said they did not want to participate in any more workshops focused on making animal ornaments. The only highlight was finding that long-time leader Estelita had developed a whole series of really well-made chambira earrings.

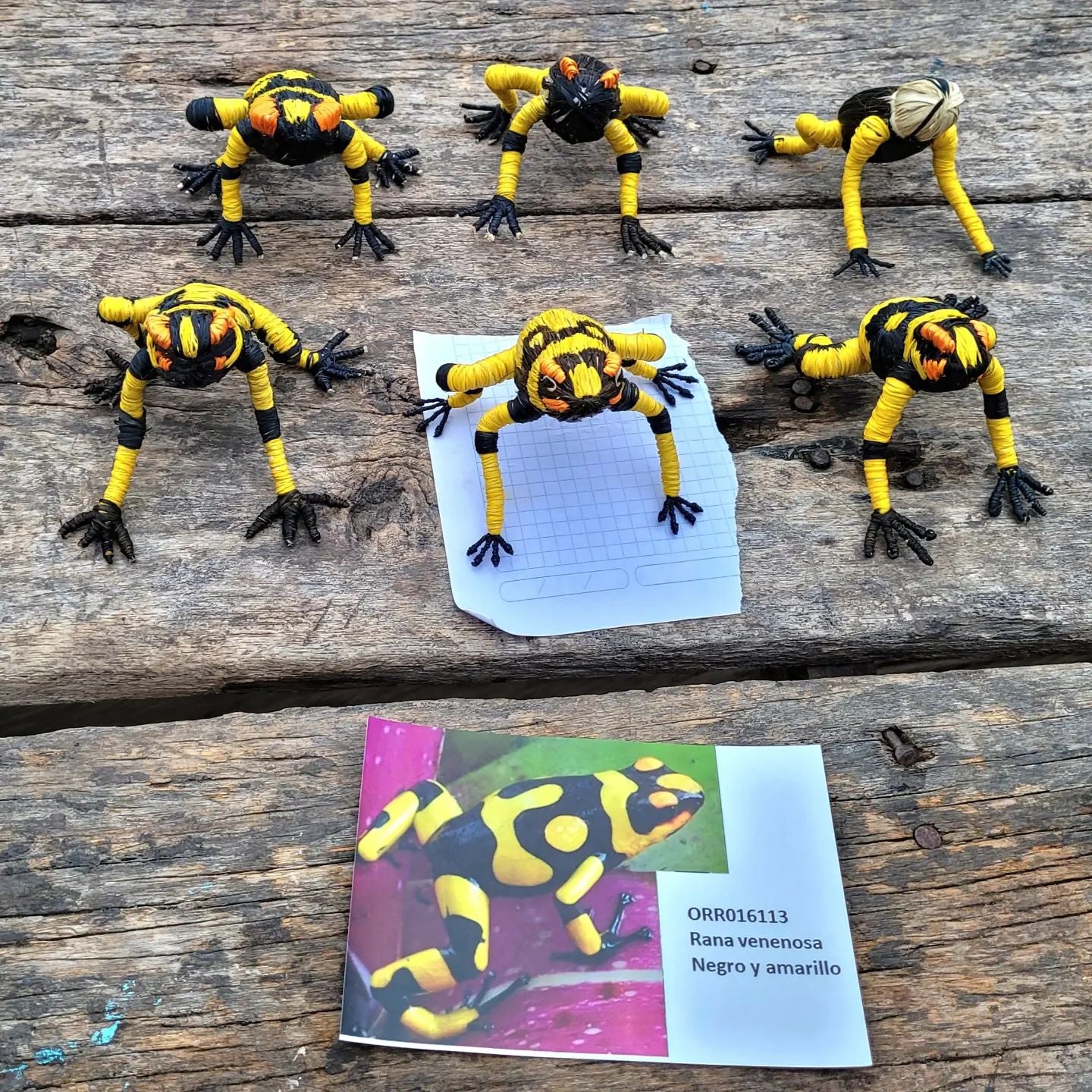

One good sign that things might be improving was meeting Chino artisan Yermeth on the streets of Iquitos a week before we were due to travel to the Tahuayo River to have introductory meetings with two other artisan communities. She enthusiastically agreed to bring an order for a large number of little frogs and some baskets back to her colleagues.

Last week, we first went to Puerto Lau to catch a speed boat to Tamshiyacu. Once again, it was fun to see the varied produce at the market and sad to see the garbage floating around the docks – not the kind of scene where Coca Cola wants to see its empty bottles being displayed. We literally jumped ship from one big rapido to a smaller one since it gave us a chance to leave sooner.

In Tamshiyacu, Andrea, Yully, Marianela and I enjoyed posing in front of the town sign proclaiming it as the capitol of pineapple, umari, and cacao. We connected with our boat driver and headed off to the Tahuayo River.

We arrived in Chino in early afternoon, and it was impressive to see the changes in Estelita’s house. Even though a health condition affecting her hands had prevented her from making crafts for several months, her creativity as an artisan and acumen running a bodega had allowed her to triple the size of her family’s little general store and buy enough solar panels to run their lights, TV and refrigerator without their gas-powered generator.

Our meeting with the Manos Amazonicas artisan group went well. I picked out some crafts to bring to the U.S., and Andrea bought some for the store in Iquitos. We placed a new order for some coasters and large woven frogs, answered questions about the current order for baskets, and mutually agreed we wouldn’t buy hot pads because our pricing needs were too far apart. Finally, some artisans seemed interested in working with us again to improve the quality of the bird ornaments they make.

I took the usual pictures of artisans with their crafts and noticed how their faces had aged a lot in the past 14 years, but their smiles were still very much intact.